Three Types of Music Analysis

Music analysis is not a single method, framework, or theory; it has many different kinds. However, most kinds of music analysis can be put into the three categories I put forward in this blog.

Below I will talk about these three types of music analysis. And for illustrative purposes, I will use them to analyse Chopin’s nocturne Op.72 No.1. If you have not heard this nocturne yet, I highly recommend Maurizio Pollini’s performance.

Type I: Structure and Characteristics

In the first type of music analysis, you analyse a musical work’s structure and characteristics, and always do this recursively.

Consider Chopin’s nocturne. At the topmost level, the nocturne as a whole has many characteristics. For example, its key is E minor, its tempo is andante, and its meter is 4/4. Also, the nocturne has certain formal structure, which is ABA’B'.

These are the nocturne’s characteristics and structure at the topmost level. However, since the nocturne has four parts, which are theme A, B, A' and B', we can continue to analyse each part’s characteristics and structure.

Consider theme A. It has many characteristics. For example, its mode is minor, and it has certain harmonic progression. Also, it has certain formal structure, i.e. theme A is a compound period, which consists of an antecedent and a consequent.1

These are theme A’s characteristics and structure. And since theme A has two parts, we can still continue to analyse these two parts' characteristics and structure.

This recursive analytic process can continue, until we meet single notes.

Type II: Generative Mechanism

If the first type of music analysis is to describe what a musical work looks like, then the second is to figure out why it looks like that.

The second type of music analysis assumes that the musical works we heard or read in scores are only superficial appearances; they are the outcomes of some beneath generative mechanisms. These mechanisms may reflect how composers manipulate and combine musical materials.

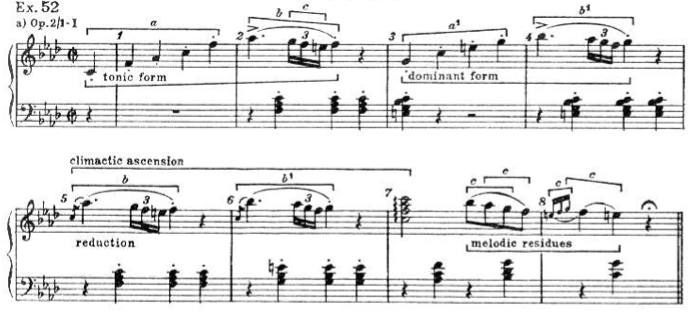

The famous composer and theorist Arnold Schoenberg is a representative of the second type of music analysis. He always took motivic development perspective when analysing music, as in his analysis of the beginning theme of Beethoven’s first piano sonata:2

In Schoenberg’s analysis, the core materials of the theme (the accompaniment is ignored here) are only three motifs, which are motif a, b and c, as indicated in the above score. In the process of generating this theme, these motifs are either repeated directly, or varied in their pitches or rhythms. These new motifs and the old ones then combine to form this theme.

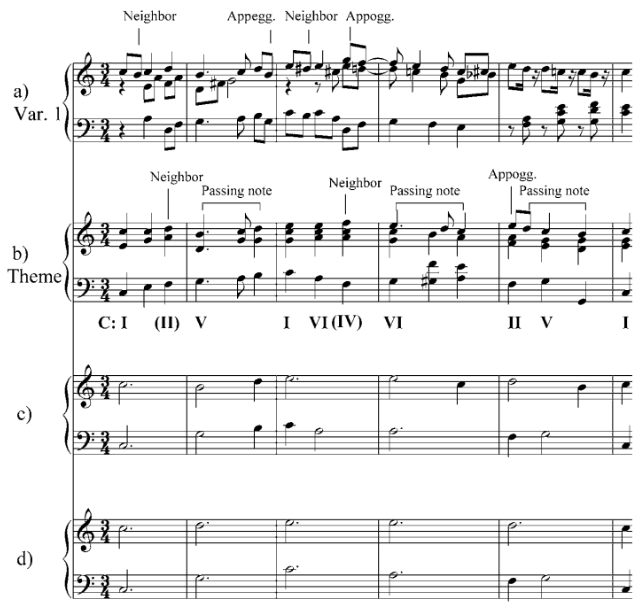

Theorist Heinrich Schenker is another representative of the second type of music analysis. He thought that by removing passing notes, neighbor notes, and other structurally unimportant notes, the deep structures of music can be revealed, as in the following example:3

In this example, from a to d, structurally unimportant notes are removed gradually, and the deep structure is revealed. Conversely, from d to a, by the process of elaboration, meaningful musical pieces are generated.

Schoenberg and Schenker have different theories, but both separate music’s appearance from its generative mechanism, and both believe that, under certain operations, music can be generated from simple and limited materials. The difference is that in Schoenberg’s theory, the operations are repetition, variation, and combination, while in Schenker’s are various elaborations.

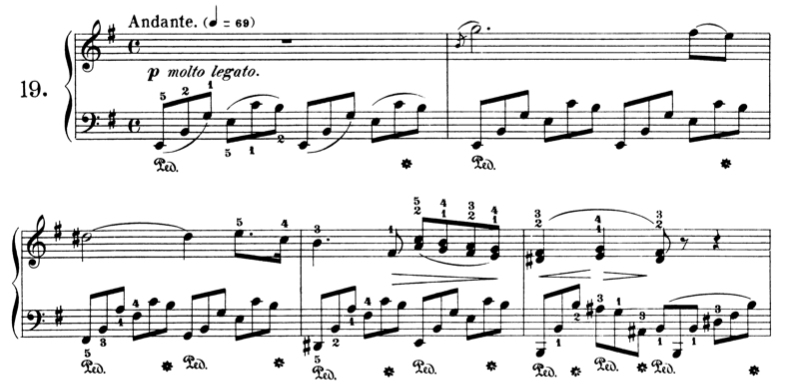

Now let’s return to Chopin’s nocturne. First, consider theme A and A'. This is the beginning of theme A:

And this is A':

Theme A' is the reprise of A, which means it is similar to A, but with some variations. For example, in A', there are a lot of chromatic notes and tuplets. The situation for theme B and B' is similar. Therefore, from the perspective of generative mechanism, we can say that

- theme A and B are the core materials of the nocturne,

- theme A' and B' are generated by varying theme A and b, and

- theme A, B, A' and B' then combine to generate the nocturne.

Now consider only theme A. As mentioned above, theme A consists of an antecedent and a consequent. Here is the beginning of its consequent:

The consequent is similar to the antecedent except for some variations, such as the movement of the melody, and the added musical line which is one octave lower than the original. That is to say, the consequent is a variation of the antecedent. Therefore, we can say

- the antecedent is the core material of theme A,

- the consequent is generated by varying the antecedent, and

- the antecedent and the consequent then combine to generate theme A.

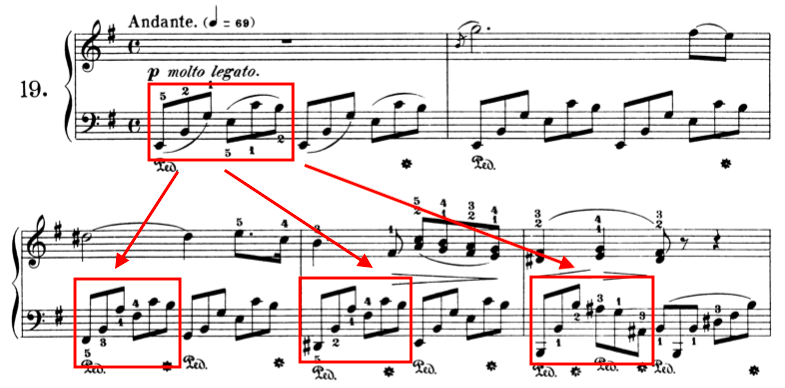

Continue. Consider the left-hand accompaniment of theme A:

We can find that almost all other motifs are variations of the first one (some of the motifs are indicated by red squares in the above score). Similarly, we can say

- the first motif is the core material of the accompaniment of theme A,

- the other motifs are generated by varying the first one, and

- all these motifs then combine to generate the accompaniment.

So far, you may have found that, the whole nocturne can be generated with only limited core materials, under some operations.

Type III: Semantics

If the first two types of music analysis are about music’s syntax, then the third type is about its semantics. In this blog, by semantics I mean the images, emotions, feelings, and other subjective experiences evoked by music.4 This type of music analysis tries to find out the musical foundations of certain subjective experiences. For example, some music makes you feel sad, maybe because it is in minor mode or it has slow tempo.

Subjective experiences are, subjective. That is to say, it is hard to describe or categorize subjective experiences objectively, especially when they are subtle or complex. For example, what does it mean when I say some music makes me think of an image of cold black fire? As a result, the third type of music analysis is inevitably hard to systematize or formalize. Also, different people may have totally different subjective experiences towards certain music, thus this type of music analysis is highly individualized.

However, the third type of music analysis is very important, especially for composers who try to imitate the music they like. For example, if you want to compose music like Olivier Messiaen’s, you have to study his modes of limited transposition.

Let’s go back to Chopin’s nocturne. There are three passages of this nocturne that give me strong feelings.

The first passage is the first six notes or the first accompaniment motif:

This motif sets the cold and sad mood for the whole nocturne. Musically, the last two notes may contribute the most to this feeling.

The second passage is the end of the antecedent of theme A:

This passage is a bridge connecting the antecedent and the consequent. It also has the cold and sad feeling, but makes it gradually stronger. And when the consequent comes out, this feeling is raised to a higher level. Musically, the ascending three-note melody may contribute significantly.

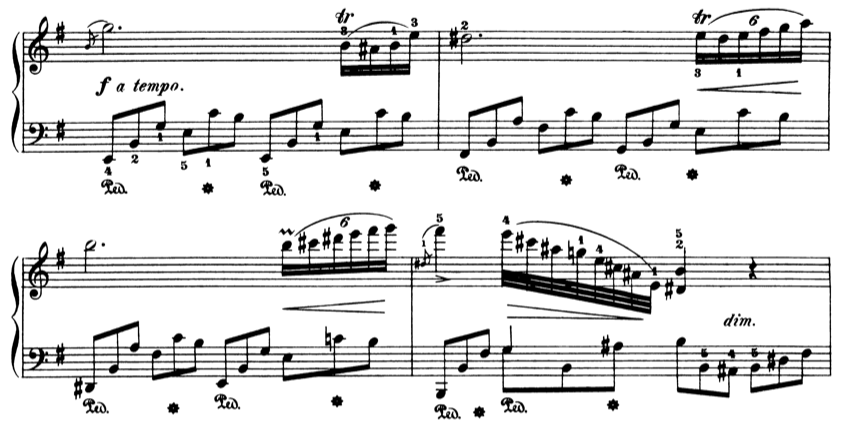

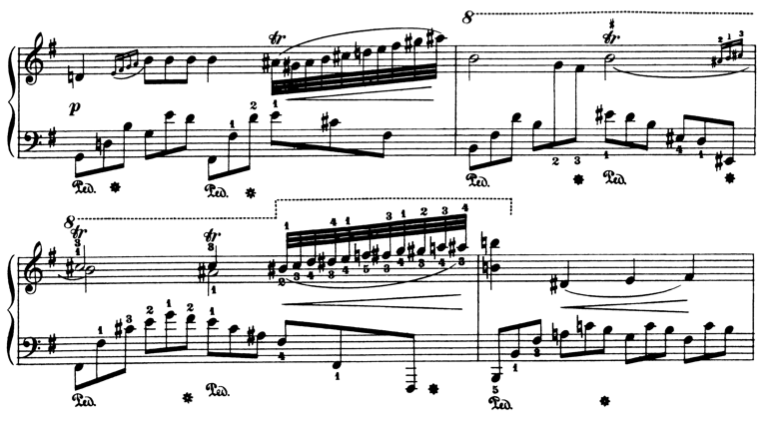

The third passage is theme A'. Here is an excerpt:

In this passage, the previously suppressed emotions burst out, with great intensity. Musically, the chromatic notes, tuplets, trills, and ascending melodic motion obviously contribute to this feeling.

However, there are also passages which convey feelings that I do not like. For example, theme B has some sweet and hopeful feeling, because of its major modality, which I think harms the prevailing sad and cold mood.

It is worth to point out that the passage towards which you have strong feelings, is not necessarily important from the perspective of structure, generative mechanism, or creativity. For example, the last two notes of the accompaniment motifs are surely replaceable, as long as the new notes are harmonically suitable.

-

Caplin, W. E., & Caplin, W. E. (2013). Analyzing classical form: an approach for the classroom. Oxford University Press. ↩︎

-

Schoenberg, A., Stein, L., & Strang, G. (1967). Fundamentals of musical composition (p. 63). London: Faber & Faber. ↩︎

-

Pankhurst, T. (2008). SchenkerGUIDE: a brief handbook and website for Schenkerian analysis (p. 11). Routledge. ↩︎

-

Juslin, P. N., & Sloboda, J. A. (2013). Music and emotion. In D. Deutsch (Ed.), The psychology of music (pp. 583–645). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-381460-9.00015-8 ↩︎